Drama Conventions

In the Hexham Hospital Garden commission, Dorothy introduced a range of tasks to enable the Commission Team (or “Commissioners”) to explore and reflect on the value and meaning of the garden for its users, or potential users. And in these tasks, she used different drama conventions.

Dorothy defined 33 dramatic conventions which could be deployed in the classroom to slow down the action, and explore meaning in depth. You can read about the conventions here.

The team decided to undertake a survey, to find out people's views about the new garden. They identified four venues where the interviews would take place.

Leaflets were produced, to explain the purpose of the survey to interviewees. "But the real problem was waiting for us," Dorothy recalled. "How could we make people stop and be interviewed by us?" After all, "it may seem strange that people come and ask what you think about the new garden of the hospital; people may not be aware of such a thing, and naturally they may not have anything to say."

In one session, the space (the drama room) was set out in different areas: “The Co-op,” “Tescos,” “Outpatients” and “Hexham Market Place.” Each "venue" contained a couple of chairs and a table on which there were questionnaires and pens. “Queen Elizabeth High School Garden Commission” was written on the card beside each table. The group worked in teams, one for each “venue.”

Around the walls, at the start of the session, people were standing in position, as “effigies.” This is drama convention no. 4: “The role present as in ‘effigy’, but with the convention that effigy can be brought into life-like response and then returned to effigy.” The “effigies” were performed by some of Dorothy's former students, including her colleague (and later biographer) Gavin Bolton. They represented different members of the community, including “various ‘elderly’ people with shopping bags and walking sticks, dressed warmly for a March day in Hexham”.

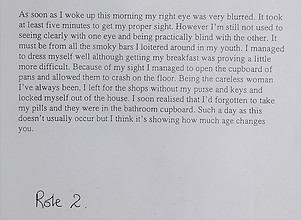

Significantly, each of the "roles" was given their own personal "story" - such as, "Someone who is in a hurry and wants to catch up with his rehearsal in the theatre." Here are some of the notes that Dorothy produced for the different “roles”:

Role 1: As soon as I woke up this morning my right eye was very blurred. It took at least five minutes to get my proper sight. However I’m still not used to seeing clearly with one eye and being practically blind with the other. … Such a day as this doesn't usually occur but I think it’s showing how much age changes you.

Role 2: … My job then was modelling but it went down the toilet when I lost my hearing in my right ear. I couldn’t hear what my agent was saying and he told me it wasn’t working and I had to give up my job. … I’m losing my left ear for hearing. Soon I will probably not be able to do anything else. ...

Presently the different “roles” entered the various venues or “shops.” The children tried to stop them, to persuade them to take part in the survey. (This is an example of Convention No. 1: “Role actually present, naturalistic, yet significantly behaving, giving and accepting responses.”)

After a time, the task was stopped by Dorothy – and the “shoppers” were invited to state what their experiences had been in the various venues. Were people courteously treated? Were explanations clear? Were the questionnaires easy to read and complete? This can be seen as an example of Convention No. 7: “The role as a portrait or effigy, but activated to speak only, and not be capable of movement”; or perhaps No. 25: “Voice of a person overheard talking to another – informal language, i.e. a naturalistic tone.” Dorothy’s aim was surely to encourage in the team a sense of what she called the “self-spectator”: i.e., an awareness of the needs of the client, which “makes everyone aware of why these things have to be done”.

Gavin Bolton said he liked the way "they showed the model of the new hospital, I found it really interesting and useful because I didn't know it would be such a big hospital." One of the "roles" said he had difficulty hearing the questions; and the team recognised they would have to consider this problem in noisy shop environments. Following the session, the team revised their plans for the survey; and succeeded, in the end, in interviewing hundreds of people.

On one level, this may seem simply like a rehearsal for the actual survey that was done later in real venues around Hexham. In part, Dorothy's aim was to encourage the Commissioners to engage in real conversations, and avoid the danger of people feeling "interrogated." But it seems that she was also aiming to go deeper. The roles she invented each had their own needs, their own life-story. She used drama conventions, in fact, to stress the human, the affective dimension. Rather than simply thinking about “blind” or “partially sighted” as a group, for example, the children encountered the "roles" as individuals.

The drama took them deeper, through the experience of empathy. Kathy White-Webster, a teacher who worked closely with Dorothy on the Garden commission, observes that the session “helped the students to see the different concerns garden users might have and to engage the heart in relation to different human contexts.”

There’s another level. From the moment when the students entered and encountered the “effigies” arranged around the wall, Dorothy conceived the session as theatre. She structured and shaped it, almost like a playwright, through different drama conventions. And her notes show that she devised the “roles” as characters, much as a playwright would. As she herself observed on one occasion: “If the teacher thinks theatre in the classroom, they won’t go far wrong.”

The use of conventions also created shifts in the group’s perspective – from looking at the “effigies” from the outside, as “Other”; to encountering them in “now” time; to hearing and seeing things from their point-of-view.

For more on the use of drama conventions in the Commission Model, see here.

This account is based on Dorothy's article; "A Vision Possible" (Drama, Winter 2003); and "Dorothy Heathcote’s Creative Drama Approaches" by Özen / Adıgüzel (Creative Drama Journal, 2010); as well as some of Dorothy's personal working notes.